Vampires have been an influential figure in English literature since Lord Byron made the mythical demon famous in his poem The Giaour (1813) in which the hero is cursed to feast on the blood of his family. Furthermore, it was in John Polidor’s The Vampyre (1818) that the aristocratic vampire was created in the author’s mockery of Lord Byron. It is the characteristics of Polidori’s vampire that society still associates with the monster today as his vampire is rich, seductive and holds a power dominance over women: ‘Aubrey’s sister had glutted the thirst of a VAMPYRE!’ (Polidori, p. 23). For this reason, vampires are traditionally associated with male characters, however, what this blog will explore is the representation of vampiric women and how their experiences have been interpreted as transgressive due to their sexual appetites and their low status in the social hierarchy.

In English vampire literature, there is a theory that the character of Geraldine in Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s poem ‘Christabel’ (1816) is an early depiction of a female vampire due to Coleridge’s reference to vampiric figures and vampire folklore (Morrison et al, p.xi):

The lady sank, belike through pain,

And Christabel with might and main

Lifted her up, a weary weight

Over the threshold of the gate: (Coleridge, ll.129-132)

Geraldine, having been found in the forest by Christabel, is crippled with pain as she reaches the boundary of the castle. Christabel is required to carry Geraldine across the threshold of the castle walls suggesting vampiric qualities in the mysterious women, as vampires share an association with the Devil, and they must be invited in (Grossberg, p.145). In regard to liminal theory of thresholds, Christabel allows for Geraldine to ‘pass through the space between’, and thus, enables Geraldine’s demonic, supernatural powers into her home (Hennelly Jr, p.205).

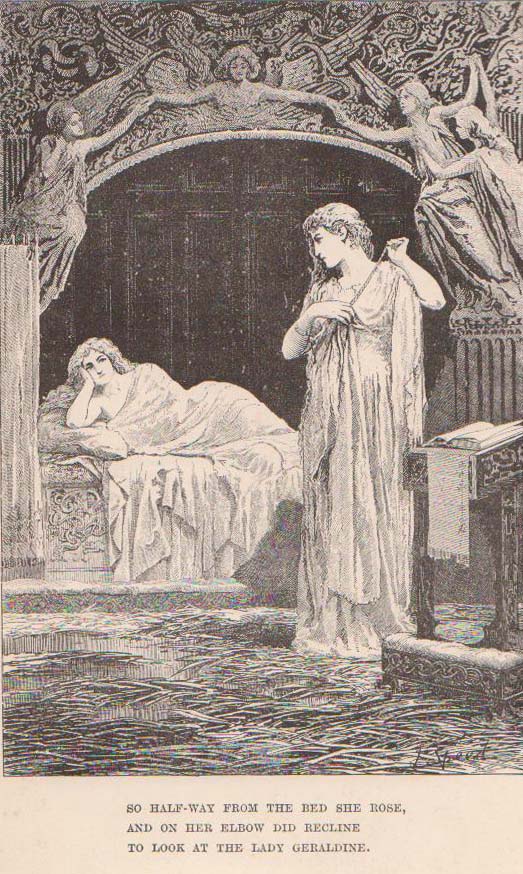

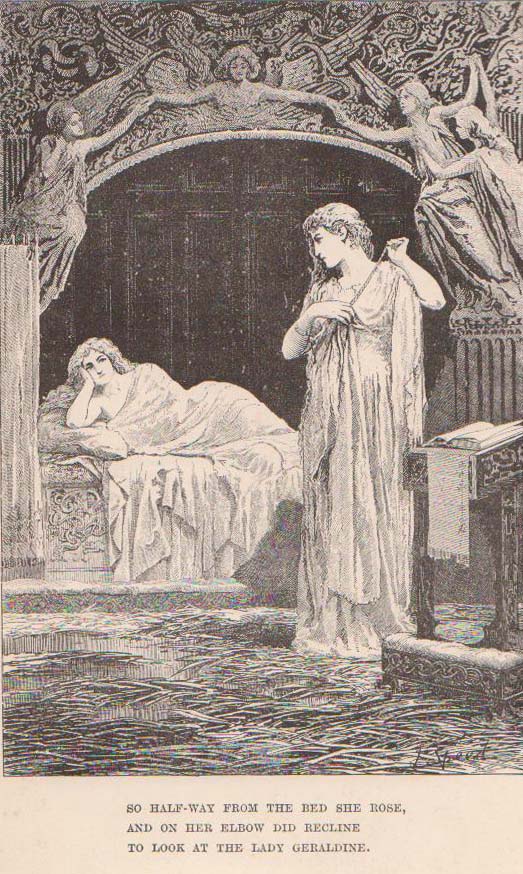

Jerrold E. Hogle’s theory that women in Gothic literature are trapped between contradictory pressures and impulses (Hogle, p.9) can be seen in the intimate scene between Christabel and Geraldine in lines 286-291 of the poem. It has have been argued by Grossberg that Christabel and Geraldine share a lesbian sexual encounter, in which the two young women sharing a bed leads to a manipulation of gender roles, as the virgin Christabel breaks tradition and gives in to her sexual desires. This manipulation of gender roles can be identified in Christabel’s reaction to Geraldine’s palms being pressed upon her breasts: ‘And both blue eyes more bright than clear,/Each about to have a tear’ (Coleridge, ll.290-291). These lines can be interpreted as Geraldine having caused Christabel’s tears through making her orgasm, thus, Geraldine takes on the masculine role as the dominant ‘male’ lover. Furthermore, Victoria Amador has described the encounter between the two women as a lesbian eroticism that was ‘codified as violent and transgressive’ (Amador, p.9), due to Christabel experiencing hallucinations after the intimate experience. It is through Christabel’s sexual encounter with Geraldine that Christabel’s sins begin to be imposed and her lack of sexual purity is arguably a reasoning for Christabel’s father’s sudden lack of affection towards her.

Image: Christabel watching Geraldine dress after their sexual encounter

This transgression of female characters, due to their sexuality, has become a popular theme in English vampire literature and can also be seen in Bram Stroker’s Dracula (1897). In the novel Stoker makes reference to female vampires: the three brides of Dracula, and the immoral hold they can have upon men. Maurice Hindle, in his introduction to Dracula states that the terror that haunt’s Stoker’s work is ‘a male fear of, yet desire for, sex’: (Hindle, p.xxi). Thus, the ‘primal scene’, where Jonathan Harker is approached and seduced by ‘sexually hungry vampire women’ is iconic to the novel, and despite Stoker’s multiple revisions, the scene’s ‘soft pornographic content’ remained similar throughout his drafts (Hindle, p.xxxiv):

‘There was a delicate voluptuousness which was both thrilling and repulsive, and as she arched her neck she actually licked her lips like an animal, till I could see in the moonlight the moisture shining on the scarlet lips and on the red tongue as it lapped the white sharp teeth.’ (Stoker, p.45)

Jonathan, who is narrating this scene via his journal, describes Dracula’s bride as having ‘licked her lips like an animal’ suggesting primal and unnatural qualities too her, as she displays her desires for the flesh. The animalistic nature of the bride’s actions also provides her with inferior qualities not just as a monster, but also because of her sexual appetites, thus suggesting she is not a respectable woman. The inferiority of vampiric women can also be seen by Jonathan describing the experience as ‘thrilling and repulsive’. The female vampire may be able to fulfil Jonathan’s sexual desires, ‘I closed my eyes in languorous ecstasy and waited – waited with a beating heart’ (Stoker, p.45), however, to try and fulfil her own is not acceptable. This is supported by Victoria Amador, who has described the representation of Dracula’s brides as being ‘an almost deliberately indefinable mutuality of sexual evil and degradation’ (Amador, p.9) as they are associated with the Victorian ideology of a fallen woman.

Image: Keanu Reaves’ Jonathan Harker being seduced by Dracula’s brides in Francis Ford Coppola’s Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992). © Columbia Pictures

Due to the epistolary style in which the novel is written, all representations of Dracula’s brides are expressed from a male perspective and in favour of the male gaze. Thus, the vampire woman are as much victims to patriarchy as other female characters. Before the brides can claim Jonathan, Dracula appears and presents his hold over the women: ‘How dare you cast your eyes on him when I have forbidden it?’ (Stoker, p.46). The women cower in fear from their patriarch and submit to his will as they move their attentions from Jonathan and accept his gift of a crying baby for them to feast upon.

The dichotomy of the sexless and sensual woman can be seen in the comparison between the previously explored representation of Dracula’s brides and the representation of Mina Murray, Jonathan’s fiancée and later wife. A clear misogyny is made towards Dracula’s brides as Jonathan refers to them as ‘awful women’ whilst Dr Van Helsing speaks fondly of Mina: ‘She has a man’s brain – a brain that a man should have were he much gifted – and a woman’s heart’ (Stoker, p.250). Mina is described as having the intelligence of a man, appealing to patriarchal values of male dominance above women, whilst also possessing a woman’s heart, presenting her with the feminine weaknesses of love, compassion and needing to be saved by men. Mina is the only woman whose diary is present within the novel, thus, suggesting she is the model image of a Victorian women in the technologically evolving end of the nineteenth century. Therefore, the concept of vampire women being lesser than the traditional woman is further enforced as the traditional woman aids and works alongside patriarchy rather than being subjected to it. Conversely, Dracula’s brides can be viewed as threatening male power via their exploitation of the male character’s repressed sexual desires.

Furthermore, ‘patriarchy involves upholding the supposed priority of the male’ which poses a negative message about the position of women (Bennett and Royle, p.182). Elaine Showalter suggests there is a clear representation of male gender anxieties and the mutilation of women’s bodies in the treatment of Lucy’s body, once she becomes a vampire, and is killed by her fiancé Arthur (Showalter, p.181):

Arthur placed the point over the heart, and as I looked I could see it’s dint in the white flesh. Then he struck with all his might. […] The Thing in the coffin withered; and a hideous, blood-curdling screech came from the open red lips. (Stoker, p.230)

Showalter refers to Arthur having killed Lucy with his ‘impressive phallic instrument’, and that the attack on Lucy was all male oriented, presenting an ideology that women can be mutilated and attacked by male forces, if they are deemed to be ‘evil’ (Showalter, p.181). Furthermore, having become a vampire, Lucy is dehumanised by being referred to as ‘The Thing’. The men find no qualms in praising Arthur’s ‘heroic’ act, as Lucy, like Dracula’s bride’s, falls to the very bottom of the social hierarchy.

Image: Lucy’s death depicted in in Francis Ford Coppola’s Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992). © Columbia Pictures

Overall, the presence of the female vampire, in the Gothic tradition, has allowed for the exploration of gender, sexuality, race and class, within the vampire myth (Amador, p.8). It is evident in both ‘Christabel’ and Dracula that vampiric women are associated with evil and sexual qualities, which undermines their social status within society’s hierarchy. Both representations of female vampires possess a homosexual sexuality which is viewed as transgressive. In Dracula, male characters dominate over female vampires and are allowed to exploit their bodies as they desire. Conversely in ‘Christabel’, Geraldine is not dominated by a male force, however, her sexual encounter with Christabel leads to Christabel’s father’s rejection of his daughter. Thus, vampiric women are represented as sexually immoral and evil creatures that are not worthy of respect – traits also associated with Lucille in Crimson Peak (2013) which will be discussed in the following blog.

Bibliography:

Amador. Victoria, ‘Dark Desires: Vampires, Lesbians and Women of Colour’, Gothic Studies, Vol 15 (2013)

Bennett. Andrew & Royle. Nicholas, The Introduction to Literature, Criticism and Theory, Fourth Edition, London: Routledge, 2014

Coleridge. Samuel Taylor, ‘Christabel’ (1816) in Halmi. Nicholas, Magnuson. P and Modiano. R (eds), Coleridge’s Poetry and Prose, London: W. W. Norton & Company, inc, 2003

Grossberg. Benjamin Scott, ‘Making Christabel: Sexual Transgression and implications in Coleridge’s ‘Christabel’’, Journal of Homosexuality, Vol 41 (2001)

Hennelly Jr. Mark. M, ‘“As Well As Fill Up The Space Between”: A Liminal Reading of ‘Christabel’’, Studies in Homosexuality, Vol 38 (1999)

Hindle. Maurice, ‘Introduction’ in Stoker. Bram, Dracula, London: Penguin Classics, 2003

Hogle. Jerrold. E (eds), The Cambridge Companion to Gothic Fiction, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002

Morrison. Robert and Baldick. Chris, ‘Intoduction’ in Polidori. John, The Vamprye and Other Tales of the Macabre, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997

Polidori. John, The Vamprye and Other Tales of the Macabre, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997

Showalter. Elaine, Sexual Anarchy: Gender and Culture at the Fin-de-Siècle, London: Virago Press, 1992

Stoker. Bram, Dracula, London: Penguin Classics, 2003

Cover Image: Lucy (Dracula 1992) ©2015-2017 dvodihalica